Reviews: New books this January

Dino Buzzati's The Bewitched Boureois, Antonio Di Benedetto's The Suicides, and more.

Hi! I’m Michael, a book critic and writer from Boston. For many years, I've contributed reviews to publications including The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and The Millions, among others, and my short fiction about aspiring ghosts, trivial psychics, and petty saboteurs has appeared in journals such as Smokelong Quarterly, Cheap Pop, and Bull. I'm currently querying my first novel. Wish me luck.

I’m also a two-day Jeopardy! champion—

—and, as a result, a somewhat useful meme that shows up on social media every so often.

I’ve started this Substack in the hopes of covering books that I wasn’t lucky enough to place in an actual publication. Oftentimes, the books I’m most excited about are the hardest to place, and it can be frustrating to not be able to write about them. I’m also interested in highlighting titles from niche or small presses, as well as works in translation (though not exclusively).

My goal is to get this critical diary out on a monthly basis, sifting through the galleys I receive for things worth mentioning. I’ll also be doing a separate series that will touch on old favorites. Already, looking ahead through 2025, I see a lot of great potential—a lot more than last year, where it felt like publishers kind of gave up on the second half of the calendar, perhaps assuming the election would drown everything else out.

So here goes:

The Bewitched Bourgeois by Dino Buzzati

Translated from the Italian by Lawrence Venuti (NYRB, January)

Buzzati has often been compared to Kafka or Borges, but I think New York Review Books was right on when invoking The Twilight Zone in their marketing copy for this new collection. Throughout the 50 stories collected in The Bewitched Bourgeois, I found myself imagining many of them as premises for the show—short, twisty, allegorical, and with a deep appreciation for the ironies and absurdities of modern life. While Kafka’s work is marked by a grim existentialism and Borges’s by his lofty, academic style, Buzzati’s stories are distinguished by a wry, cynical sense of humor, one that keeps the little puzzles he crafts entertaining throughout—his stories are often laugh-out-loud funny.

I think today you’d call what Buzzati does “speculative fiction.” He borrows tropes from science fiction, fantasy, metafiction, and magical realism to craft literary tales that speak to anxieties both existential and personal. In “The Gnawing Worm” (1952), the narrator is plagued by a simpering acquaintance who subtly takes advantage of social niceties to exert control over him. What begins as a comedy of manners evolves into a horror story. “The Prohibited Word” (1956) imagines a conversation between two friends in a censorious society in which compliance is compelled indirectly, and finds Buzzati using the construction of the story itself to pull the rug out from under the reader at the last minute in an astonishing reveal.

I was deeply charmed by The Bewitched Bourgeois; I feel like I’ve found something of a kindred spirit in Buzzati, whose stories felt precisely tuned to my own sensibilities as a reader and as a writer. I love a well-crafted surprise, and these stories are full of clever touches. I’ll definitely be reaching back to check out The Stronghold (a.k.a. The Tartar Steppe) and The Singularity.

The Suicides by Antonio Di Benedetto

Translated from the Spanish by Esther Allen (NYRB, January)

I didn’t really like The Silentiary (NYRB, February 2022), so I was surprised by how much I enjoyed The Suicides. A cheeky picaresque about a rakish journalist tasked with figuring out whether there’s any connection among a rash of suicides in late-60s Argentina. Funny, thoughtful, and engagingly intertextual, with a dash of conspiracy to keep things interesting. It vaguely reminded me of The Crying of Lot 49, though I don’t want to overstate the similarity. It’s a quick read, too.

Vantage Point by Sarah Sligar

(MCD, January)

I was a fan of Sligar’s debut, Take Me Apart (MCD, 2020; Read my review here), a #metoo-era psychological thriller that explored the suspicious death of a pioneering feminist artist. In Vantage Point, Sligar offers readers another taut mystery—Clara Wieland is the scion of a prominent, obviously Kennedy-inspired political dynasty whose history is marked by tragedy; when a deep-faked video of her threatens to derail her brother’s budding political career, she must overcome her own checkered reputation to uncover who is threatening her family.

This one didn’t grab me; I admit I bailed pretty early on after bumping up against what I felt was a pretty tacky reference to T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland. Sligar presents readers with a faux Wikipedia entry for the “Wieland curse,” the popular shorthand for the series of tragedies that have befallen the Wielands throughout history, always in the month of April. In the entry, it’s speculated that the famous opening line from The Wasteland is, in fact, a reference to the Wielands. Somebody tell Chaucer.

Stray thoughts

I’ve been dipping into the galley for Andrea Long Chu’s Authority (FSG, April). Finding out that she’s a fan of the SCUM Manifesto finally made her whole style click for me. Provocative, playful, incisive, hyperbolic, a little dangerous… joking, but also maybe deadly serious? It’s helped me appreciate her takedowns a little more—I thought her Lapvona-induced criticism of Ottessa Moshfegh was insightful, even if I did ultimately disagree with her conclusion.

Is there anything more dangerous than precocious teen who stumbles upon the wrong book at the wrong time? Sheluyang Peng’s “Nietzsche’s Eternal Return in America” (American Affairs, Winter 2024), is a virtuosic deep dive into the philosopher’s ever-evolving presence in the history of American culture and also a diagnosis of a lot of the weird, far-right thought swirling around the darker corners of the internet. This essay has everything: Goth teenagers turned Catholic reactionaries, Leopold and Loeb, the Scopes Monkey Trial, Pieter Thiel...

I’ve been enjoying

’s “Forty Years of Dalkey” series, and was pleased to see Noëlle Revaz’s extraordinary With The Animals highlighted. I was lucky enough to review the book for The Boston Globe when it came out in 2012. It’s a harrowing story with a unique voice. I think about it often.

What I’m reading for February

Lion by Sonya Walger (NYRB, February 4)

Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield (W.W Norton, February 11)

Radio Treason: The Trials of Lord Haw-Haw, the British Voice of Nazi Germany by Rebecca West (McNally Editions, February 11)

The Revolutionary Self: Social Change and the Emergence of the Modern Individual, 1770-1800 by Lynn Hunt (W.W. Norton, February 18)

Morgan Falconer’s How to Be Avant-Garde: Modern Artists and the Quest to End Art (W.W. Norton, February 18)

Malaparte: A Biography by Maurizio Serra, translated from the Italian by Stephen Twilley. (NYRB, February 25)

Recently reviewed

This past November, I spoke to Nate DiMeo, author of The Memory Palace: True Short Stories of the Past (Random House, November ‘24), for

.“Since 2008, DiMeo has plumbed the murky depths of the past for his podcast, which sheds light on obscure people and oddball events that have fallen through the cracks of our collective memory.

And here on Substack, I took a quick spin through a number of 2024 titles, including some personal favorites, like Fiona Warnick’s Skunks (Tin House, April ‘24) and Fien Veldman’s Hard Copy (Apollo, September ‘24).

Upcoming reviews

January

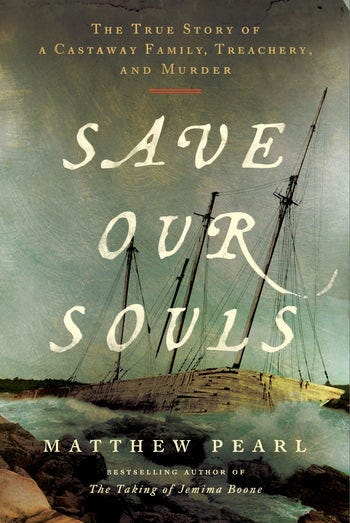

For WBUR: Save Our Souls: The True Story of a Castaway Family, Treachery, and Murder by Matthew Pearl (HarperCollins, January) — Tales of fraud and malfeasance in 19th century merchant sailing practices.

For WBUR: At Dark, I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca (Blackstone, January) — “Look at me, suburban dung,” Manson told Wesley. “Does this shock you?”

February

For WBUR: From Ted to Tom: The Illustrated Envelopes of Edward Gorey by Edward Gorey, edited and with an introduction by Tom Fitzharris (NYRB, February) — Letters from camp.