“Yes, the honors pile. But I want gossip, sexual intrigue, back-biting and hair undoing. I want women, confidences, confessions & broken hearts. Dissipation, indiscretions, glitter, dash, sparkles, sin.” — Clement Greenberg, in a private letter, 1940.

When reading about artists, it’s lovely to learn about their work and their process. But what really keeps those pages turning is all the sordid details of their exciting, bohemian lives.

I recently received a galley of Sue Prideaux’s Wild Thing: A Life of Paul Gaugin (May, W.W. Norton), which purports to dispel some of the more scurrilous misconceptions about the artist’s life—we’ll see about that. That, and my recent review of Morgan Falconer’s How To Be Avant-Garde in the Boston Globe, got me thinking about some of my favorite artist-centric books.

So here are six that I think are worth checking out. And if you stick around till the end, I’ll highlight a few upcoming 2025 titles that are on my agenda, too.

The Man in the Red Coat by Julian Barnes

If you're like me, you love literary and artistic gossip from France's Belle Epoque.

Well, Julian Barnes's The Man in the Red Coat, reads like a highbrow, late-19th century issue of the National Enquirer. This book has everything: Torrid affairs, wanton murder, celebrity trials, ether-drinking Satan worshipers, and loads of French dandies and aesthetes trying to outdo one another in debauchery and excess.

The eponymous "man" is Dr. Samuel Pozzi, celebrity gynecologist to the stars and "disgustingly handsome" Parisian playboy known to his admirers as "Doctor God" or "Doctor Love." He's acquainted with all the biggest names in the beau monde, and through him we get to spend time with Marcel Proust, Sarah Bernhardt, J.K. Huysmans, etc. Much time is spent with his close friend, Count Robert de Montesquiou, the infamous inspiration for Proust's Charlus, Huysmans's Des Esseintes, and Lorrain's De Phocas.1

Barnes was inspired by the arresting portrait of Pozzi by John Singer Sargent, and the book reveals Pozzi to be a pretty great guy considering all the insanity he was surrounded with: A forward-thinking doctor who introduced modern techniques and patient-focused care to France and made gynecology a respectable profession; a rationalist, atheist Dreyfusard; a thoughtful, anti-nationalist cosmopolitan. He was in many ways ahead of his time. Barnes's prose is cheeky and fun, a perfect fit for the outrageous subject matter. Highly recommended.

The Grand Affair by Paul Fisher

Fisher’s book is a serious work of scholarship, written in masterfully engaging prose—but he’s also particularly interested in exploring the uncertainty around Sargent’s love life, as well as the politics and culture surrounding same-sex relationships of the era.

With the increasing acceptance of LGBTQ identities in contemporary culture, there is an effort to look back in search of historical figures whose sexuality was suppressed or written out of the historical record. Indeed, many of Sargent’s contemporaries clandestinely engaged in what would today be considered queer relationships and left documentary evidence to that effect.

In Sargent’s case, there’s no hard proof, but plenty of compelling, circumstantial evidence that he may have been involved with same-sex partners. Though he did have relationships with women, they were spotty and short-lived; in contrast, he had very personal, long-term associations with several men, including the artist Albert de Belleroche and models Nicola d’Inverno and Thomas McKeller (of whom a striking nude is on display at the MFA). It’s very possible that these men were his lovers.

The one quibble I have with Fischer is that he claims Sargent’s paintings of women lack any erotic charge whatsoever. I strongly disagree!

Oh and guess who shows up:

The Shores of Bohemia by John Taylor Williams

This book is as a wild as its subjects. Fifty years of art and free love on the shores of Cape Cod, covered in painstaking detail.

“The Shores of Bohemia'' is eager to pay homage to the legendary work of its brilliant subjects, but at its core, it’s more kaffeeklatsch than salon. While there are thoughtful deep dives into the Bauhaus aesthetic, the emergence of Provincetown as a haven for gays and lesbians, and elaborations on the nuanced political distinctions among the Cape’s Stalinists, Trotskyites, and anarchists, you can tell Williams really enjoys dishing. Sometimes it pushes ahead of the work: Joan Colebrook, who wrote five books and contributed to The New Yorker, is described as being “famous for her erotic connection to men.”

Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life by Diana Greenwald and Nat Silver

Published in collaboration with the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the book is circumspect about Mrs. Gardner’s personal activities. It does not, for example, touch on a rumored dalliance with John Singer Sargent mentioned in The Grand Affair. It does, however, explore her eccentric habits, as well as her long and controversial companionship with F. Marion Crawford, a man 14 years her junior (and nephew of her close friend, Julia Ward Howe).

Gardner cultivated a flamboyant public persona that made her the talk of Boston society and a target for scurrilous rumors that have made it hard to separate fact from fiction. In the book, Greenwald and Silver reproduce an illustrated news clipping that shows her walking through the Boston Public Library alongside a tame African lion and relate a story where she shocked the staid audience at Symphony Hall by showing up to a performance wearing a Red Sox hatband. “That Mrs. Jack Gardner should resort to such sensational methods to keep herself before the public eye,” declared a 1912 Town Topics column, “[it] looks as if the woman has gone crazy.”

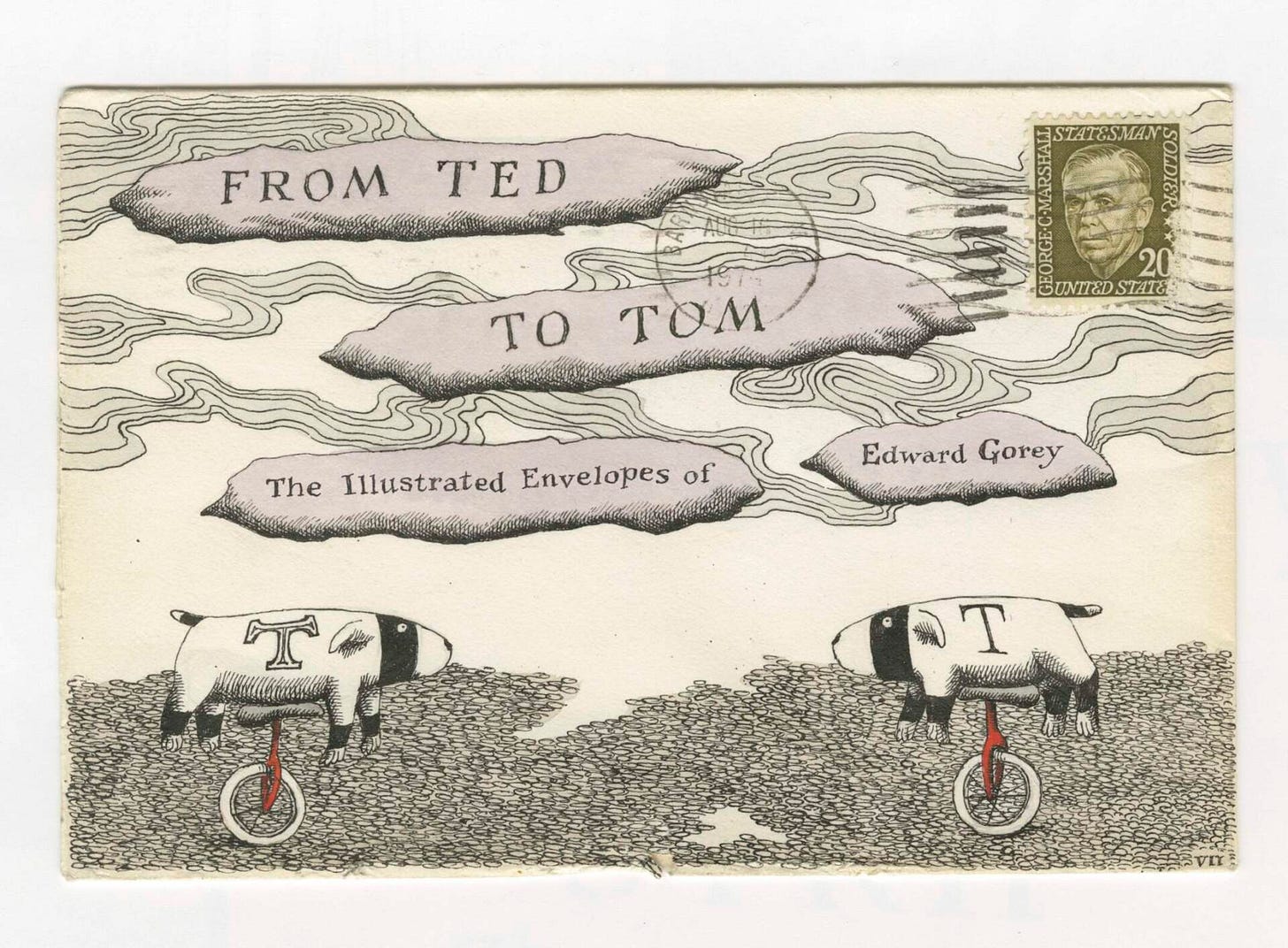

From Ted to Tom by Edward Gorey (ed. Tom Fitzharris)

An intimate look into a brief, yet intense friendship between two men. Tom Fitzharris, to whom Edward Gorey sent at least 50 elaborately illustrated envelopes to over an 18-month period in the mid ‘70s, grants readers a look into the artist’s day-to-day thoughts, reproducing not just the envelopes, but also the personal letters Gorey wrote him.

But we only see one side of the exchange. And this absence invites us to speculate on what the full scope of their relationship may have been and how, after such a fervent flurry of correspondence, it suddenly came to such an unceremonious end:

In time, Gorey and Fitzharris fell out of touch. One day, after a long period of silence, Tom received an unsigned letter, declaring that “one can’t predict when things will end, or how they’ll run their course.” It was obviously from Gorey, though a far cry from the laboriously personalized missives of ‘74 and ‘75. It’s a bittersweet denouement to this once-intense friendship. But Fitzharris looks back at his time with Gorey warmly, noting that despite his gloomy artistic oeuvre and grim public persona, Gorey was a warm, playful companion and a delight to be around.

Paris in Ruins by Sebastian Smee

Smee posits an unrequited love affair between the married Edouard Manet and his painterly peer and occasional subject Berthe Morisot. (Who ultimately married Édouard’s brother, Eugène. Awkward.) With them as his focal point, he takes readers into the heart of the impressionist movement, and the result is dizzying.

Blending art criticism, military history, and biography, Smee shows how the traumas of the Franco-Prussian war and the horrors of the Paris Commune of 1871 profoundly affected the development of impressionism. He depicts a movement struggling to find its way in a beleaguered nation torn apart by extremists on both ends of the political spectrum. Deeply researched and written in a propulsive, almost cinematic style. His conclusion, that the impressionists deliberately cultivated an apolitical, in-the-moment style in reaction to the excesses of both the hard left and hard right, is intriguing, especially today.

Coming up in 2025

April: Elaine Sciolino’s Adventures in the Louvre: How to Fall in Love with the World's Greatest Museum (W.W. Norton) takes a look at the past and present of the famous museum. (I’m a few chapters in and it’s pretty interesting so far).

May: Paul Elie’s The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s (FSG) and J. Hoberman’s Everything is Now: Primal Happenings, Underground Movies, Radical Pop and The 1960s New York Avant-Garde. (Verso). Decades of decadence.

June: Lauren O’Neill-Butler’s The War on Art: A History of Artists' Protest In America (Verso). Au courant.

July: Henry Wiencek’s Stan and Gus (FSG), a look at the relationship between architect Stanford White and sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and Anika Burgess’s Flashes of Brilliance: The Genius of Early Photography and How It Transformed Art, Science, and History.

From Wikipedia: "He had no affairs with women, although in 1876 he reportedly once slept with the great actress Sarah Bernhardt, after which he vomited for twenty-four hours. (She remained a great friend.)"

How do you not include Ruth Brandon's Surreal Lives?

"Paris in Ruins" was my favorite art history read last year—I absolutely loved Smee's writing. Thanks for the great recommendations!