The pure products of America

On Sinclair Lewis's "Babbitt," the persistence of prejudice, and being just in an unjust world.

1.

as if the earth under our feet

were

an excrement of some skyand we degraded prisoners

destined

to hunger until we eat filth

— William Carlos Williams, “To Elsie” (1923)

2.

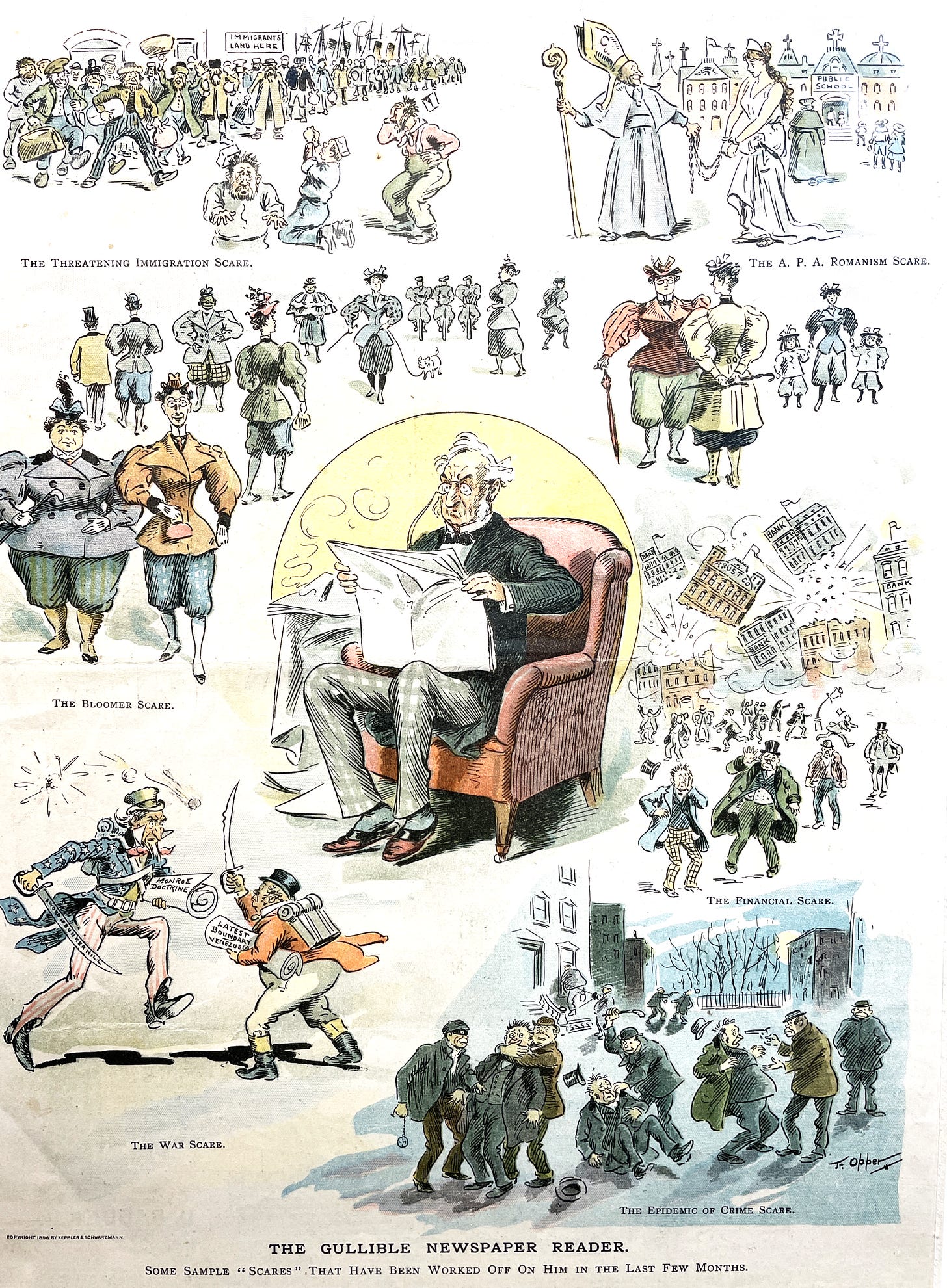

A few years ago, I was browsing the prints at Commonwealth Books in Boston’s Downtown Crossing when I came across a striking political cartoon from an 1896 edition of Puck magazine.

Some of the details are period specific—the squared-off paper hats1 worn by the working-class men, for instance, or the chance that we might go to war against Britain over Venezuela. But with a little light editing and some updated artwork, there’s no reason this cartoon couldn’t run in a contemporary magazine satirizing the moral panics and political propaganda of today.

Hordes of immigrants coming to take Americans’ jobs, cities overrun with violent criminals, women defying traditional gender roles, teachers indoctrinating our children with radical ideologies. It’s all quite familiar. Except that back in 1898 the immigrants in question were from Italy and eastern Europe, the sign of an unwholesome gender-bending woman was the wearing of trousers, the radical ideology allegedly being fed to the children by their teachers was Catholicism,2 and the criminals lurking in our cities’ dark allies were thought to be Irish.3

The well-dressed swell in the center of the cartoon certainly believed all these things to be true. He probably voted for McKinley over Bryant in that year’s elections, the McKinley who promised that high tariffs would lead to broader economic prosperity. But the editors of Puck and, presumably, the illustrator of this cartoon, Frederick Burr Opper,4 knew that this was all a bunch of bunk meant to scare people into a reactionary frame of mind.

Almost 130 years on from this cartoon, it seems absurd to us that anyone would be roused to apoplectic anger by a woman wearing trousers or led to believe that the United States was threatened with destruction because their child’s kindergarten teacher was a Catholic. But we can’t be too dismissive of our forebearers. The same playbook is still in effect today, just with slightly different targets. And we’re still falling for it. Maybe a century from now, people will look back at our contemporary angst over gay, lesbian, and trans people and Haitian or Latin American immigrants with as much confusion and condescension as we view the prejudices of 1896. One can only hope. But if history is any guide, those future Americans are likely to have their own prejudices, too—ones that, while different in detail, might possibly still fit within the structural framework of xenophobia, gender anxiety, and classism outlined by Opper’s cartoon.

When I see something like this print, I have mixed emotions. First, despair that we’re still struggling with these same prejudices, albeit in different forms, so many years later. But I would typically try to counter that with the belief that, if people only knew how far back these prejudices go and how silly the past iterations of them seem, they would realize that the ones they hold today are just as ridiculous. I’ve long thought that if only people knew the history and had the right information, they might change their attitudes and see things in the present a little more clearly.

I’m not so sure I believe that anymore.

3.

I recently read Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt (1922), a novel that strikes many of the same notes as Opper’s cartoon. Is Babbitt the Great American Novel? I would argue that it might be the Definitive American Novel, as it seems to capture something timeless about this nation’s neuroses and prejudices. About the very fabric of its being.

George F. Babbitt is a middle aged, middle class realtor in Zenith—the Zip City—a booming mid-sized metropolis somewhere in middle America. He lives a middling life of modest comfort and has a place of middling esteem among the conservative business interests and elites who run things around town. He’s worried that his daughter, recently returned from college, is becoming a socialist, and that his son dreams of becoming a movie star instead of something more practical and respectable. His marriage is moribund—we learn he only ended up betrothed to Myra because he is incapable of actually expressing his feelings and desires—and he recalls bitterly his young, thwarted dreams of pursuing the law and going into politics.

Babbitt is a man of means who, nevertheless, feels he is not afforded the respect he deserves. He believes he has been prevented from achieving the heights of success or renown that he is actually capable of. He tries to stifle these feelings, and succeeds for a time. But when a close friend—truly, his only real friend—experiences a break that leads him to lash out violently at his wife and ends with him sentenced to prison, Babbitt is given a preview of what might be in store for him if he continues to ignore his feelings of restlessness and inadequacy. He becomes disillusioned with his comfortable life and begins searching for something more meaningful. But he hardly knows where to begin, and much of the book is spent watching him flail around desperately for something to hold onto, things that directly challenge the pieties of the hidebound world he’s come to know: liberal-progressive politics, extramarital relationships, skepticism of religion and corporate America, anti-consumerism, and (relatively tame) debauchery.5

Lewis’s send-up of Babbitt’s middle class milieu is biting and hilarious; but what makes Babbitt more than a broad satire of easy bourgeois targets is that Lewis shows, with something approaching sympathy, exactly how hard it is to resist the smothering conformity of the American status quo and how easy it is to go along with what everybody else is doing even though deep down you know it isn’t what you want, or even what is right.

Babbitt’s fundamental weakness is that he is susceptible to flattery and chafes against direct challenges to his personal agency. He is desperate for esteem and is constantly seeking external validation of his own importance. That is his driving force: Status anxiety and personal insecurity drive his ideological choices. The most important thing is that he feels important. What he’s arguing for or against matters little, as long as it puffs up his ego.

His radical turn isn’t motivated by a newfound sense of justice or a rational weighing of the facts; rather, it’s a congenial encounter with the socialist activist Seneca Doane, the bête noire of Zenith’s business class, that sets him off. Doane, a former college classmate of Babbitt, compliments George and even goes so far as to credit him with inspiring his own progressive worldview.

I remember—in college you were an unusually liberal, sensitive chap. I can still recall your saying to me that you were going to be a lawyer, and take the cases of the poor for nothing, and fight the rich. And I remember I said I was going to be one of the rich myself, and buy paintings and live at Newport. I’m sure you inspired us all.

With Babbitt’s faith in his middle class conservatism faltering, Doane gives him a newfound sense of purpose. “He felt daring and idealistic and cosmopolitan,” writes Lewis. But again, it’s all about how it makes Babbitt feel. It’s never about whether the thing itself is good or bad or right or wrong. His old friends, the conservative elites of Zenith don’t take kindly to this turn toward progressivism, but their efforts to bully Babbitt into submission only make him dig in his heels. He doubles down on his open-mindedness, speaking out in favor of labor unions and protests and expressing his dissatisfaction with the trappings of his middle-of-the-road life. But for all the excitement that comes with being a man alone, a modern day Diogenes, it’s a lonely path. Babbitt has made himself a pariah.

Late in the book, a brush with mortality shakes Babbitt. The old gang, having learned their lesson, approach George with a more conciliatory attitude. They appeal to his need to feel important, his desire for belonging. The resolution is every bit as sad and horrifying as Winston Smith’s capitulation at the end of 1984.

Then did Babbitt, almost tearful with joy at being coaxed instead of bullied, at being permitted to stop fighting, at being able to desert without injuring his opinion of himself, cease utterly to be a domestic revolutionist. He patted Gunch’s shoulder, and next day he became a member of the Good Citizens’ League.

Within two weeks no one in the League was more violent regarding the wickedness of Seneca Doane, the crimes of labor unions, the perils of immigration, and the delights of golf, morality, and bank-accounts than was George F. Babbitt.

But Lewis doesn’t end the book on a sour note. In what amounts to an epilogue, we see Babbitt still retains some of his newfound radical spirit, and though he feels it’s too late for him to buck the system, he’s more understanding of his children’s more modern perspective and hopes that they might escape the fate to which he’s succumbed.

In between the agony of George F. Babbitt, Lewis provides insight into the prevailing sentiments of 1920s America which, unfortunately, are not so unlike ones you’re likely to see on Twitter/X or in the pages of some reactionary centrist magazine today. On a train ride, Babbitt overhears the conversation of two traveling salesmen:

“Now, I haven’t got one particle of race-prejudice. I’m the first to be glad when a n***** succeeds—so long as he stays where he belongs and doesn’t try to usurp the rightful authority and business ability of the white man.”

“That’s the i.! And another thing we got to do,” said the man with the velour hat (whose name was Koplinsky), “is to keep these damn foreigners out of the country. Thank the Lord, we’re putting a limit on immigration. These Dagoes and Hunkies6 have got to learn that this is a white man’s country, and they ain’t wanted here. When we’ve assimilated the foreigners we got here now and learned ’em the principles of Americanism and turned ’em into regular folks, why then maybe we’ll let in a few more.”

At one point, a labor strike paralyzes Zenith. The National Guard is called out to put the strike down, led by one of Babbitt’s chums, Clarence Drum, a shoe salesman.

Captain Clarence Drum came swinging by, splendid in khaki.

“How’s it going, Captain?” inquired Vergil Gunch.

“Oh, we got ’em stopped. We worked ’em off on side streets and separated ’em and they got discouraged and went home.”

“Fine work. No violence.”

“Fine work nothing!” groaned Mr. Drum. “If I had my way, there’d be a whole lot of violence, and I’d start it, and then the whole thing would be over. I don’t believe in standing back and wet-nursing these fellows and letting the disturbances drag on. I tell you these strikers are nothing in God’s world but a lot of bomb-throwing socialists and thugs, and the only way to handle ’em is with a club! That’s what I’d do; beat up the whole lot of ’em!”

Truly, some things never change.

Lewis is masterful in Babbitt. It’s funny, touching, and incisive; a sympathetic portrait of a flawed man that doubles as a comprehensive and well-argued indictment of a whole culture. And, of course, its power comes from its continued relevance. Like Opper’s cartoon, with some light editing and some updated slang, you could probably publish it today and nobody would blink an eye.

4.

In recent years, I’ve been thinking a lot about my values—what they are, how I came to hold them. I’m not religious, but I attended a Jesuit catholic high school and college and one of the core lessons of Jesuit teaching is the idea of being a “man for others.” Broadly speaking, this means being a person who prioritizes the needs of those less fortunate than you over your own needs. At the time, I can’t say how much I engaged with this idea directly, but now that I’m older, I recognize that I definitely internalized it to some degree, perhaps more than I realized. I can certainly see its influence in my personal life and in my politics. But I think I allowed myself to believe that this perspective is more common than it is and not something that I owe specifically to my upbringing and education.

Last year, I saw a political advertisement that really drove this home for me. It was an ad for Kelly Ayotte, the Republican candidate for governor of New Hampshire—really, it was a negative ad against her opposition, Joyce Craig. (Ayotte won the race.)

The ad concerned the problem of homelessness in Manchester, where Craig was mayor. I don’t live in New Hampshire and can’t speak to the situation in Manchester or Craig’s policies. I live in Massachusetts, so I just have to sit through the New Hampshire ads because we share a media market. But I was really taken aback by the tone of the ad.

The problem of homelessness in Manchester, according to the ad, was not that people in Manchester were homeless, it was that Craig had been too considerate of the homeless people in her city, which allegedly led to general disorder—needles, drugs, and feces on the streets. The ad features a man who identifies himself as a former police officer and current bar owner who says that “Joyce put the needs and care of the homeless before us.”

I understand being frustrated with the downstream, negative effects of homelessness on public spaces, which has certainly been more pronounced in the post-COVID era. But I really can’t imagine how someone could feel comfortable saying what that bar owner said—she put the needs and care of the homeless before us—and not be ashamed to say out loud or to even think it. It’s one thing to argue that her efforts might have been wrong-headed, ineffective, or counterproductive. It’s quite another to suggest that caring about the least fortunate among us is itself a transgression. Solving homelessness is hard and expensive. Few want to do what it takes to remedy the situation at its root, and are instead content to simply move unhoused people around so they’re out of sight. It appears many New Hampshire cities are resorting to ultimately futile public camping bans to address the specific concerns of bar owners like the one in that ad instead of making an effort to actually solve the underlying issues.

I don’t know, something about that ad felt, to me, like a new and sinister crack in the social contract. In the past, I feel like people at least pretended to have altruistic or constructive aims when peddling reactionary rhetoric. To see something like that completely laid bare, unvarnished was disturbing.

In any case, it led me to reflect on the “man for others” ideal. And I realized I hadn’t actually read the thinking behind it, the 1973 speech by Fr. Pedro Arrupe. It is, naturally, quite Catholic and churchy. But aside from that, the central conceit, I think, should be accessible to everyone. And the image of the world that Arrupe lays out in his speech is not unlike the one that Lewis constructs in Babbitt.

For the structures of this world – our customs; our social, economic, and political systems; our commercial relations; in general, the institutions we have created for ourselves – insofar as they have injustice built into them, are the concrete forms in which sin is objectified. They are the consequences of our sins throughout history, as well as the continuing stimulus and spur for further sin.

…

The “world” is in the social realm what “concupiscence” is in the personal, for, to use the classical definition of concupiscence, it “comes from sin and inclines us to it.”

Essentially, the nature of the world we live in—that we have constructed for ourselves—makes it easy to do the wrong thing. To prioritize our own well-being over others, to dehumanize those who are not like us, to seek out luxury and indulge in overconsumption. The social and personal rewards for doing the wrong thing are significant, and the penalties for trying to do otherwise can be severe. That’s what Babbitt found out when he dared to be different. His friends took his efforts to improve himself as a critique of their way of life. And that’s what made it so easy for him to fall back into the fold when push came to shove.

What is difficult is to be good in an evil world, where the egoism of others and the egoism built into the institutions of society attack us and threaten to annihilate us.

Arrupe’s recommendation does not solve for this. His prescriptions—living simply, refusing to draw profit from unjust sources, resisting unjust structures from within rather than stepping away from them, and doing all these things while eschewing the kind of hateful ego-centric anger that the world will inevitably turn on us—ask us to swim against the current. They are prescriptions for conflict—interpersonal, internal, and ethical conflicts. It’s a tough row to hoe. He does not say it will be easy. In fact, he rather explicitly says we will more than likely not succeed.

The struggle for justice will never end. Our efforts will never be fully successful in this life. This does not mean that such efforts are worthless.

I think that might be the most important point. There will never be a time where we will not have to struggle for justice—against the world and against ourselves. There will never be a final victory over the prejudices that seem to recur time and time again throughout history. Whatever gains we make must be zealously guarded, whatever progress occurs requires constant vigilance. You can’t ever stop. And given all that, it’s no wonder that many people decide it’s not for them and give in to self-interest and rally around those who tell them it’s alright to look out for yourself and not worry about others.

But what Arrupe makes clear is that it isn’t just a consequence of circumstance—it’s a choice you make. And it’s a choice you have to make every day.

5.

it seems to destroy us

It is only in isolate flecks that

something

is given offNo one

to witness

and adjust, no one to drive the car7

The American Protective Association was an anti-Catholic organization who campaigned to ban Catholics from teaching in public schools. From Wikipedia: “Most all of the better class of immigrants are Protestants. It remains that, almost entirely, the lowest class are Roman Catholics.... Among these are mostly found the train wreckers, robbers, plunderers, murderers, and assassins of the country.... In the large cities criminal statistics show that while Roman Catholics furnish about four percent of the population, they produce more than one-half of the crime, if we except those cities in which there is a large percent of negro criminals.”

The hoodlums in the drawing have the simian countenance typical of racist depictions of the Irish in 19th century cartoons.

One of Opper’s cartoons is believed to have been the first to use the term “fake news.”

For a contemporary version of this story, see my review of Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection.

An old-fashioned slur for Hungarians.