The Sleepers by Matthew Gasda (Skyhorse/Arcade, May 6, 2025)

When a publicity representative from Skyhorse reached out to me a few months ago to pass on a galley of Matthew Gasda’s The Sleepers, I wasn’t sure it was something I’d be interested in.

Gasda, a playwright and former high school English teacher, has made a name for himself in recent years through his association with the anti-establishment (some might say crypto-fascist) Dimes Square scene in downtown Manhattan; by writing articles bemoaning cancel culture and virtue signaling for magazines with a distinctly right-leaning political slant, such as UnHerd or Compact; and now by publishing a book with Arcade,1 an imprint of Skyhorse—a press that has a reputation for publishing right-wing agitprop, conspiracy theories, and books from “controversial” authors, like Woody Allen’s Apropos of Nothing or Blake Bailey’s Cancelled Lives.

The book’s marketing copy revealed that the story concerned, in part, an elder Millennial Marxist professor who is stuck in a doomed relationship and resorts to “courting” (how quaint) one of his students in the months ahead of the 2016 election.

As I considered the galley, an idea of the novel began to form in my mind, cobbled together from this collection of circumstantial evidence—I imagined a self-consciously heterodox book about left-wing hypocrisy; about the failures of the Bernie left and the transgressions of the professional-managerial class; about how navel-gazing liberals, beholden to urban identity politics, were caught off-guard by the rise of MAGA; about the gray areas of sexual power dynamics and age gap relationships, the excesses of #MeToo—stuff like that. Not really my thing.

But the publicity representative had sent me a nice, personalized note. (I assumed he’d seen my review of Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection and thought this was in the same ballpark.) And the book is only like 290 pages, so I figured I’d give it a shot.

Well, I read Matthew Gasda’s The Sleepers and must report: It is, in fact, a strikingly conventional book. I spent the whole time waiting for the other shoe to drop. But in the end, the book was just a relatively normal work of literary fiction about a hapless couple in a bad relationship. Spare, well-observed, and engaging.

I actually liked it.

But I have some thoughts.

Dan & Mariko & Xavier & Eliza

We meet Dan, a professor, and Mariko, an actress, at an especially low point in their relationship. Having moved in together after a whirlwind year-long romance, they now find themselves getting on each other’s nerves. The passionate sex that sustained them through the early days has become infrequent and disappointing. Mariko’s career aspirations have foundered, while Dan has found some success as a writer in left-wing circles. They appear to be experiencing a mid-life crisis a couple of years early. (Mariko’s sister Akari and her girlfriend Suzanne pop up occasionally, too.)

In a moment of self-doubt, Dan responds to a Facebook message from one of his students, Eliza. She convinces him to sneak out to meet her at a bar, where they engage in probing repartee—alternately flirty and defensive. The night ends awkwardly, with Dan’s expectations of a no-strings-attached hookup dashed. But the potential remains, and Dan and Eliza keep their chat going, each trying to work up the courage to finally go through with it.

At times, the book reads like a play—long sections of dialogue with minimal description. You can see how it would work well on stage. And it works fine on the page, too, for the most part.

Into this tangled web comes Mariko’s former lover and mentor, Xavier, probably the most compelling character in the book. He’s older, a cultured producer of plays who has been stricken with cancer and is looking for once last dalliance with his former flame before the illness robs him of his vitality. Unlike our cast of Millennials, he moves with purpose, speaks with passion, and has little regard for social conventions. He exudes an adult authority that feels beyond what Dan or Mariko are capable of.

“You have to realize I don’t care at all about your bourgeois relationship,” Xavier tells Mariko.

When I read this, I couldn’t help but laugh. Xavier, man—that’s basically the whole book.

(The chapter about Xavier and Mariko reminded me of another book, which I’d recommend reading ahead of this one—Alyssa Songsiridej’s 2022 debut Little Rabbit. You can check out my review of it at WBUR.org.)

Yadda, yadda, yadda

So, curiously, the parts of The Sleepers that you would think would constitute the “climax” of the book—Dan’s commencement of an affair with Eliza, his breakup with Mariko, and the disintegration of his career once his transgression is revealed—occur off-stage, in an elliptical edit. Three years elapse between the end of part 1 and the beginning of part 2, apparently enough time for Dan and Mariko’s estrangement to have thawed enough that they can go catch a movie together and have a calm, collegial discussion about what went wrong.

Perhaps this kind of time jump would work well in a stage production; in the book, it comes off as a little bit of a cop out. Maybe Gasda rightly assessed that he wasn’t up to depicting a drawn out Title IX investigation against Dan, but still—he passed up an opportunity for some genuine drama.

Instead, we get the main characters reconstructing what we missed through dialogue. Which is fine. But in some respects, the two parts of The Sleepers feel like a prologue and an epilogue to a meatier middle bit we never get to see.

Identikit politics

The Sleepers is mainly concerned with how we as individuals construct false identities for ourselves or, perhaps more accurately, have them forced upon us by social expectations and mores. While those identities can help us succeed within a narrow, socially acceptable framework, they may ultimately stifle our deepest desires and prevent us from realizing our true selves.

Take Dan, for instance.

Dan, a writer and college professor, has made a name for himself among his leftist peers. How has he done this? Well, he began by affiliating himself with the anti-establishment (some might say anarchist) Occupy Wall Street movement in downtown Manhattan. He followed that up by writing articles bemoaning capitalism and fascism for a magazine that had a distinctly left-leaning political slant, N+1. And when we meet him, he’s set to publish a book with Verso—a press that has a reputation for publishing left-wing agitprop, critical theory, and books with “controversial” themes, like Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline or Sophie Lewis’s Abolish the Family.

Hmm.

“He couldn’t see,” writes Gasda, “that his intellectual posture was not, as he believed, a product of his ideological purity, but rather a behavior that he had acquired in order to flourish in the… marketplace.”

Oh.

Had he always been trying to deceive other people about who he was?

And if so, why? Why couldn’t he let himself be seen? What was he afraid of?

This higher-level thought, or self-criticism, never really went away: it was the shadow cast by the quarter-truths with which he constructed his persona.

I see.

Well, then.

All the world’s a platform

The game-layer of life was more interesting than life itself2

This air of phoniness suffuses the book—Mariko and Akari’s parents are “California fake progressive,” supposedly disappointed that Akari is dating a woman. Akari’s interactions with Suzanne are described as “manufactured… they both knew that it was basically artificial, that nothing would change.” Dan “was a Marxist (or claimed he was),” though he holds Tesla stock and harbors a secret desire to own one someday.

At its core, The Sleepers imagines that most people are faking it—that whatever one’s stated motivations and values, people are first and foremost self-interested, concerned with their own material well-being and relative social status. Everyone is playing a role, hiding behind a constructed personality that serves to insulate them from the pain of actually being perceived, but prevents them from enjoying the true happiness of genuine connection. It suggests that real freedom lies in dropping the facade and just admitting that you never really cared about all that high-minded stuff in the first place. Politics just gets in the way. Of creativity, especially.

But is that true?

Here’s how Gasda describes Dan:

He was a pseudo-humanist, a pseudo-generalist; he pretended that the scope of his expertise was large, when in fact, it was miniscule. He knew a few things about Marx and nineteenth century literature, and beyond that, he was basically a philistine—not that he would ever admit it.

A big deal is made about how Dan claims to only like Lars Von Trier films, because it sounds erudite and allows him to dismiss everything else so he doesn’t have to engage with it. He doesn’t know much about Nietzsche, but bluffs his way through a discussion with the younger, more learned Eliza. He’s a pompous poseur, a psued. His reputation is unearned, merely the result of a canny assemblage of signifiers and received wisdom.

Xavier, in contrast, is meant to come off as truly erudite—Gasda shows this by name-checking a canny assemblage of signifiers: a “Folger edition of Cymbeline,” Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations “the 1955 edition,” Mahler’s 2nd Symphony. He is self-possessed and unconcerned with how others see him. “That nagging, pseudo-moral voice in your head that tells you to stick to conventions is not very interesting or smart,” he tells Mariko.

But what distinguishes Xavier from Dan isn’t the breadth or depth of his cultural knowledge, it’s that Xavier’s engagement with art is purely aesthetic, while Dan’s is primarily political—a lazy, almost spoon-fed way of making sense of art. Dan doesn’t have to actually form an opinion on art, or even consume it. He can just refer to his ideological programming to judge whether something is good or bad.

Are there people for whom politics (in this case, leftist politics) are merely a means of seizing the moral high ground or fashioning a personality where one doesn’t exist? Sure. Are there those for whom bourgeois morals are an excuse to pass judgment and evade self-reflection? No doubt. But there seems to be this sense that it simply isn’t possible to have sincere and strongly felt moral or political beliefs; that it’s all a self-serving fiction. And I think that’s probably a reassuring thing to believe for people who don’t have strongly felt moral or political beliefs, or would prefer not to have to think about them at all. If everyone’s a phony, then you don’t have to feel bad about not caring so much about whatever’s going on.

Last November, Gasda spoke at an event in Brussels where he talked about being shut out of the New York theater establishment because his work was “not explicitly ideological.” He says he believes there needs to be space in art and theater to interrogate a broad array of views and that it shouldn’t be purely activist in nature. I’m sympathetic to that, I suppose, in that I find overly didactic art is usually pretty weak.

According to him, his plays had a “total lack of categorizable politics” that made it hard for the gatekeepers to validate that he was on the correct side of things. They wanted a clear, progressive point of view. “I thought that being truthful and being an artist were the only things that mattered,” he says.

I haven’t read his plays, so I can’t judge.

However, he also references “[his] constant refusal to declare himself [in the culture wars].”.

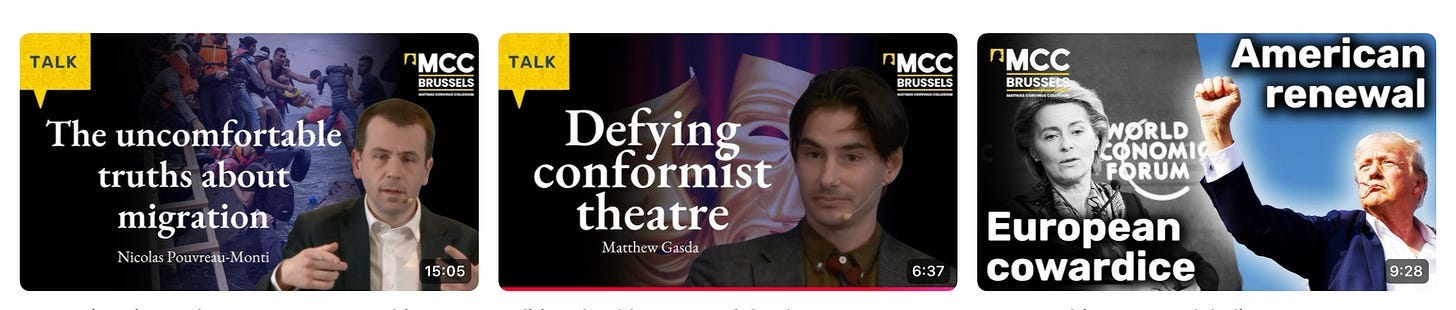

He said this at the Mathias Corvinus Collegium, an educational institution with close ties to Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban, as part of an event titled “Creativity in Chains: The Diversity Agenda.” Here are some of the other videos that sit alongside Gasda’s on the MCC YouTube channel.

I get it—if your perspective is that art shouldn’t be political, you aren’t going to get invited to a lot of leftist or progressive spaces. The fact that you will get invited to a lot of expressly right-wing or reactionary spaces, however, should probably serve as an indicator that your non-political perspective is, in fact, quite political. And if you accept those invitations, I don’t think you can go around saying that you haven’t declared yourself. Maybe those gatekeepers were onto something; maybe that non-ideological art wasn’t so non-ideological after all.

I know from Gasda’s writing (in the articles linked above) about the “Millennial virtue economy” and the “progressive panopticon” that this book is rooted in an agenda. (He expressly identifies Dan as a “Calvinist,” a pejorative he uses in the Compact article in lieu of “elitist.”) I suspect that when he talks about keeping “politics” separate from art, he only means what most people would call “progressive politics” and everything to the right of that isn’t “politics” to him, it’s what just he calls “the truth.”

You could absolutely read The Sleepers apolitically: As a nice book about a guy who sucks and gets his comeuppance. And on that level, it works. But why this particular type of guy? The answer lies in those articles.

Am I just being a Dan, forcing art into political boxes to make myself seem smart? Should I be striving to be more like Xavier and focus on the book’s aesthetics? Dan wouldn’t have bothered to read The Sleepers. Xavier might have. But given what he told Mariko, I don’t think he would’ve liked it.

Aesthetically speaking, I liked The Sleepers. It’s very much the kind of book I enjoy. But I almost didn’t read it because I was suspicious of the author’s politics and assumed that the book would be poorly written and tendentious, like the articles in UnHerd and Compact. And I was wrong—about the writing, not the politics.

It’s well written and much more subtle than those articles. But while I enjoyed it more than I expected, I wasn’t in love with the fundamental premise—that what’s going on here isn’t political at all, and that “politics” is just a weapon employed by disingenuous people who are insecure or jealous or trying to compensate for their lack of ability. There’s a case to be made about homogeneity in contemporary art and literature, but I don’t think this is it.

Ultimately, I think this aspect of the book may be too provincial—hyper specific to contemporary New York bohemians or particular to the kind of Substack writer who is preoccupied with the perceived lack of white male or “non-woke” (whatever that means) literary authors. In that context maybe it does resemble some form of local “truth.” But I’m not in either of those groups, so I don’t find it all that interesting. In that respect, The Sleepers is a bit like a fragment of an overheard conversation: fun to eavesdrop on from a safe distance, but ultimately something that I’m not a part of and probably shouldn’t try too hard to involve myself in.

Michael Patrick Brady is a writer from Boston, Massachusetts. His criticism has appeared in The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and The Millions, among others. His short fiction about aspiring ghosts, trivial psychics, and petty saboteurs has appeared in Smokelong Quarterly, CHEAP POP, BULL, Maudlin House, Flash Fiction Online, Flash Fiction Magazine, Ink In Thirds, and Uncharted. He is currently working on a novel. Find him at www.michaelpatrickbrady.com.

For more on Skyhorse and Arcade, this article on Bruce Wagner at the Metropolitan Review was pretty interesting.

There’s lots of stuff in the book about how social media is bad. Granted. Didn’t feel like writing about it. It’s pretty standard stuff at this point.

Fair review, pretty generous, really. I haven't read the book but the subject and characters of the novel don't intrigue me in the slightest; it would take a much stronger writer than Gasda to make it all interesting. Social media, millenial failure to form lasting relationships because of individualism and ambivalence, nyc dithering; wake me up when it's all over. The writing I've read in his journals and a few articles here and there strike me as dim and trite; maybe the plays are better. You've articulated a phenomenon I think I've unfortunately indulged in myself, and want to move beyond: the inadequacy of this affected pose of vocally preferring aesthetics to politics while cozying up to certain political movements or subcultural/political spheres, even relying heavily on mailed in and cynical criticism of the more facile caricatures of politically active identities, all while disavowing any preferences or prescriptions. At some point you probably just have to call bullshit. It's not impressive or convincing. While I don't think an artist needs perfectly correct and progressive opinions or politics, the refusal to grant conviction and thought to people with beliefs that challenge our own complacencies, reducing them to status signaling careerist phonies, is a kind of dismissal that should be beneath a serious artist. "People I don't like are motivated by base emotions, while I'm a pure artist who should be left alone to slander their earnest efforts" isn't an attitude all that endearing to me anymore

Good piece that I think fairly weighs the shallowness of Gasda's understanding of both art and politics. I have liked some of his meandering pieces on Substack (to my surprise, knowing he is friends with the fascists) and it often seems like he is someone who was not terribly deep on politics who fell in with people he now doesn't want to offend, but he doesn't feel the fire the way they do, and doesn't have any other attachments that pull him away from their dumb views. Maybe too much psychologizing, but his influence on this place makes me distrust his work much more than I probably would if I encountered it as just another scuffling writer.

I realize this is a tangent, but I have had the same thoughts about Pistelli, who is so beloved (and who is both erudite and generous to people, so I get why) and yet whose political analysis seems weak, even lazy (and certainly written with a deliberate opacity of syntax and word choice so as to impress as meaningful but to contain little), and whose recent novel, with all the rapturous reviews, in all the quoted excerpts reads just like the contemporary litfic that everyone here is supposedly so disgusted and tired of. And there's nothing wrong with that, but everyone has their "not enough male writers etc." blinders on and seems remarkably lacking in self-awareness about their own tastes.