Why I didn't read "Lost Lambs"

Plus: What I read instead. What I'm planning to read. And something I read a while ago.

Hello readers! In this issue:

Why I didn’t read Madeline Cash’s Lost Lambs. (Bear with me)

The soon-to-be-released books that I read instead.

What else I’m hoping to read in the coming months.

A recommendation for a great book now out in paperback.

And welcome new subscribers! Hope you stick around for a while to get a feel for things.

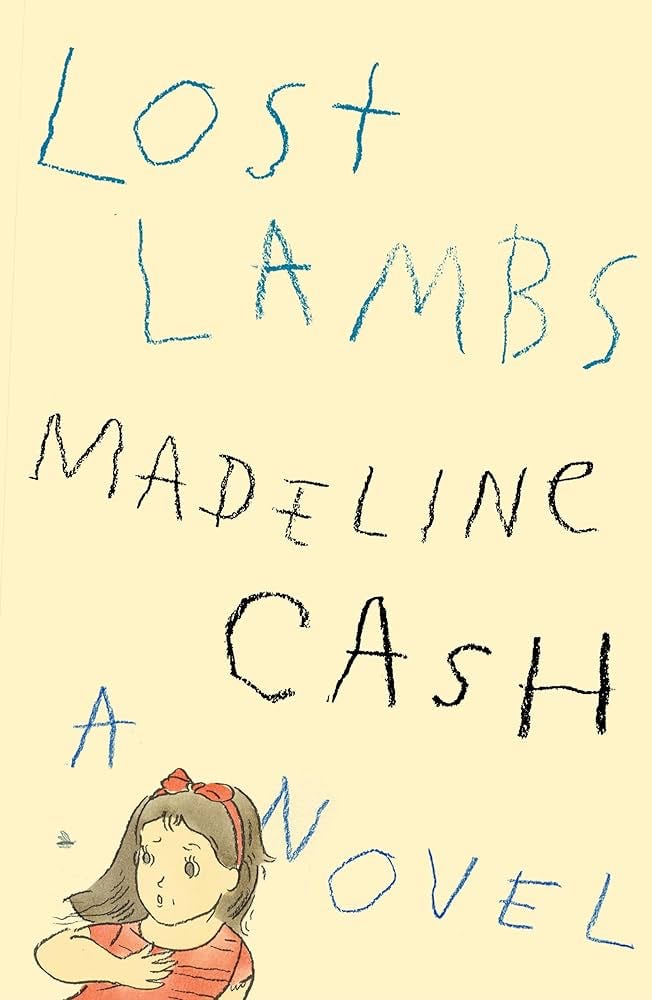

Last week, Substack was awash in takes about Madeline Cash’s debut novel, Lost Lambs—not about whether it was any good or not, but rather, whether it was worthy of so much attention. The book’s rollout was accompanied by glowing reviews and sympathetic profiles, and this apparently struck some as being “coordinated” or “manufactured” in some nefarious way.

The simpler read would be that it was coordinated and manufactured in a benign way, as part of a well-executed PR campaign, the kind you would expect a debut novel being published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux to get. I think the real implication was that Cash, a New York City literary fixture, was merely trading on her social currency and getting a leg up from her fellow New York City literary fixtures, who happen to write for the kinds of prominent publications that certain Substackers feel aggrieved about being excluded from. That may be true to some degree, but I guess I see that as more of a fact of life than something to get incensed about.

I remember when I graduated college, I was speaking to a friend of mine from high school who had gone to Harvard. He and I were from similar backgrounds and, though he went to an Ivy and I didn’t, we were also on similar post-collegiate trajectories: Good, steady, above-average jobs, but not, like “big” jobs or anything. He was telling me about a roommate of his who had been hired as a cartoonist at The New Yorker.

“Wow,” I said, amazed that this was actually a job you could get right out of college. “How did he manage that?”

“Well,” my friend said. “His grandfather founded The New Republic.”

Ah, O.K.

“It’s not what you know, it’s who you know” is an adage for a reason, and while I might lament that literary types in downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn have an advantage in the book game simply by being in close proximity to publishers and to one another, I think it’s important to keep things in perspective. Not everyone is a scion.

Years ago, I closely followed the career of another writer who I both admired and envied. They were about my age, maybe even a little younger, yet had incredible clips at very prestigious outlets. They profiled very famous people. They themselves were profiled by other writers in smaller, hipper magazines—they had a really neat loft apartment and designed crossword puzzles on the side and were generally just living a really cool, really dreamy literary life in New York. And they had talent! Their writing was good and interesting and had a strong and distinct voice. (I still follow this person, even here on Substack!) Meanwhile, I was writing reviews of digital cameras and high-definition televisions just outside of Boston, a very good gig, but not very exciting.1

I wanted to know more about this person. How did they do it? I dug into their social media accounts in an effort to understand them better, to figure them out as a person and not just a byline. And what I found was that they in fact lived a very precarious, difficult life—I think I remember an extended crisis around an abscessed tooth; this person lacked dental insurance and didn’t have enough cash on hand to cover treatment. They were struggling to make ends meet as a freelancer—the flashy magazine profiles only went so far.

It was a real eye-opener. I remember feeling silly that I had taken my own relative comfort for granted. It was an important lesson and one I’m glad I learned early enough to not let my misplaced envy make me bitter. I’ve managed to piece together my own version of a literary lifestyle, slowly but surely, and am proud of what I’ve accomplished, even if it’s relatively modest in comparison to others who had the opportunity or the guts or the foolishness or merely the good fortune and privilege to be able to make a go at it in New York.

The other thing about the kind of networking that gets you a big splashy debut campaign, though, is that in addition to being at least somewhat talented and well-connected, you probably also have to be very nice and pleasant to be around, too. Clubbable, as they used to say. I can see where that might be frustrating for you if, say, you had a well-earned reputation for being really unpleasant to people, like, shockingly, slanderously unpleasant. Talent and smarts can only take you so far. My mother used to always say to me, “It’s nice to be smart, but it’s smart to be nice.” She knew that being smart came easily to me, and while she was proud of my good grades and other academic accomplishments, she wasn’t especially impressed by them. But being nice took effort. It was something I had to—have to—work at. And I value those successes all the more, because it doesn’t come easy. Because it takes will.

But anyway, on to why I didn’t read Lost Lambs. Or, more accurately, why I only read the first chapter.

I received the galley for Lost Lambs back in August of last year, and what I typically try to do with most galleys that I receive is give them a 30-minute test drive to see if I’m interested in going the distance with them.

The first chapter of Lost Lambs follows Father Andrew, a Catholic priest who is concerned about the well-being of one of his young parishioners, the “lapsed Catholic” parochial school student Harper Flynn.

Right from the get go, something about how Cash depicted Father Andrew seemed off to me, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on it. I just had this odd sense that something wasn’t right.

Now, here’s the thing. When you receive a galley, they typically come with a warning not to use the galley text for quotations and to only use the final copy, which typically comes a few weeks before the release date, to validate quotes. Generally speaking, I think that’s fair, so I don’t want to harp on what the galley text said too much. But it did contain something that made me raise an eyebrow, something that was later replaced in the final text with something a little more innocuous. Nevertheless, I couldn’t unsee it.

I did some Googling to try and clarify what was going on. There, I learned that Cash based Harper’s ostensibly Catholic “Sacred Daughters Convent School” on her own “strict Lutheran education.”

Now, as a lapsed Catholic parochial school student myself, I have to wonder: Why did Cash make her characters and their school Catholic when it’s actually based on her Lutheran upbringing?

In any event, I felt I’d found my answer: That odd feeling I was getting when reading the first chapter was me picking up on a latent Lutheranism lurking beneath a thin Catholic veneer. I genuinely felt discombobulated by it. Maybe it sounds silly, but this just took me out of the book completely. It gave me the ick. I can’t really explain it, it just didn’t… read as Catholic. It felt strangely foreign, like I was in a denominational uncanny valley. Wouldn’t it have been easier to just keep it Lutheran? What’s the point in changing it?

(This is where someone who finished the book chimes in to tell me that there’s a perfectly good explanation for all this and if I’d just kept reading I would’ve seen that.)

Am I being too nitpicky? Maybe. Obviously, lots of people enjoyed the book and didn’t find this problematic at all. I fully admit that I am probably being excessively anal about it. But sometimes things just don’t click for some weird reason and unfortunately, this was one of those times for me. In the end, I think I’m probably more annoyed that my deep-seated Catholic programming has denied me the ability to read and enjoy what is, by most accounts, a very fun and entertaining book. And who knows, maybe one of you will convince me to give it another shot. But having read some of those positive reviews, I get the impression that even aside from its curious religious conversion this one just isn’t for me.

The soon-to-be-released books I read instead

Lost Lambs was not my only January 2026 DNF—I couldn’t get into Liadan Ní Chuinn’s story collection Every One Still Here (FSG, January) either, and I tapped out about a third of the way through Julia Cooke’s Starry and Restless: Three Women Who Changed Work, Writing, and the World (FSG, January). Not a great month for me and Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, I guess, which historically has been a favorite of mine. Oh, well

It wasn’t all bad, though. I did finish a few upcoming books that I hope to write about, here or elsewhere, in the not-to-distant future:

Beloved Son Felix: Coming of Age in the Renaissance by Felix Platter (McNally Editions, February). I’m a sucker for a good, old fashioned primary source diary. Reminds me that I need to pick up the next volumes of Chateaubriand one of these days.

Ashland by Dan Simon (Europa Editions, February). Sort of like Carolyn Kueber’s Liquid, Fragile, Perishable (My review at the Boston Globe), but about New Hampshire instead of Vermont.

A Beautiful Loan by Mary Costello (W.W. Norton, March). New Irish fiction about a woman who, through the course of her life, manages to get wrong footed by both traditional, repressive Irish culture and modern, progressive Irish culture.

Crazy Genie by Ines Cagnati (New York Review Books Classics, March). The follow up to one of my favorite books, the extraordinary Free Day.

The Vivisectors by Missouri Williams (MCD, May). O.K., so I’ve seen some very effusive praise for this from Jon Repetti and Aaron Gwyn over on Twitter, and right now my take on it is… complicated. I will say that I was definitely compelled to keep reading it, and thankfully I have a few months to sort out my feelings about it in more depth (and to read The Doloriad, which I feel I must now). I don’t want to give too much away, but if you put a gun to my head and asked me to quickly describe the book, I’d probably sputter something stupid like “What if Mervyn Peake wrote The Human Stain?”

Williams’s style here is that thing where you reference quotidian things in vague, non-specific terms to create a feeling of uncanny otherworldliness about them, so, like, she only talks about “The city” and “The university” as these remote, quasi-fantastical entities, imbued with vague portent, and I realized—hey, I’ve done that. So shameless plug, check out my short story “Recent Tragic Events” over at Flash Fiction Magazine:

Life in The City had become absurd. In the years since the war started, we’d been overwhelmed by endless memorials to the newly dead. It started out small and tasteful at first—simple yellow ribbons tied to lampposts and modest candlelight vigils. Nothing so obtrusive as to make you break your stride.

What else I’m hoping to read this year

I’m a fan of Andrew Krivak’s fiction, and his latest novel, Mule Boy, is out in February. He has a way with a sentence. Check out my reviews of his novels Like the Appearance of Horses and The Bear at WBUR.

In April, W.W. Norton is publishing Andrew Graham-Dixon’s Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found, while Viking is putting out linguist Valerie Fridman’s Why We Talk Funny: The Real Story Behind Our Accents. Fridman’s book is of particular interest to me, as someone whose intermittent non-rhoticity has caused controversy in the past. There’s also Caroline Bicks’s account of Stephen King’s early work, Monsters in the Archive (Hogarth).

In May, Isaac Fitzgerald’s American Rambler, a memoir about following in the footsteps of Johnny Appleseed (Knopf) has caught my eye, as well as James Romm’s Since You’re Mortal: Life Lessons from the Lost Greek Plays (W.W. Norton).

Beyond that, your guess is as good as mine. Let me know if you see anything I might like.

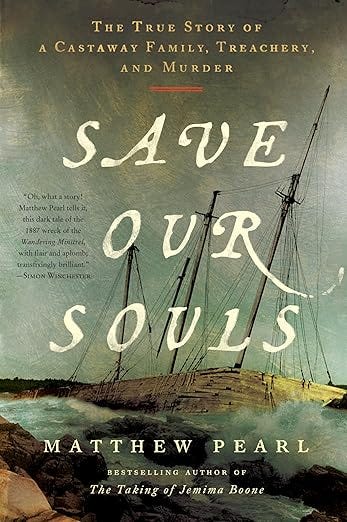

In paperback this January

Save Our Souls: The True Story of a Castaway Family, Treachery, and Murder by Matthew Pearl (Harper Perennial)

Pearl’s book is well researched and entertainingly written. It really is a tremendous story—there are shipwrecks, murders, kidnappings, buried treasures, imperialism, all sorts of maritime insurance fraud. I highly recommend it, especially for fans of David Grann or Hampton Sides.

On the night of Feb. 3, 1888, a fishing boat named the Wandering Minstrel ran aground on the coral reefs surrounding Midway Atoll, then one of the most remote and least hospitable specks of land in the Pacific Ocean. For Captain Frederick Walker, this disaster was made all the more harrowing due to the presence of his family on board — his wife, Elizabeth, and their three sons, 17-year-old Freddie, 15-year-old Henry, and 14-year-old Charlie. By luck, they managed to escape the sinking ship and in the morning washed up on Midway. Surprisingly, the family and the ship’s 23-man crew found themselves in the company of a man named Hans, who’d been stranded alone on the island sometime before.

Although I did get to go on a few wild press junkets sponsored by camera manufacturers, one of which became an anecdote I told during my Jeopardy! appearance.

I did not finish All Fours, and I can’t decide if I should tell anyone (I do want to) or just let it slide. My reasons are not as sharp as the ones mentioned above for the Lost Lambs DNF, but elaborating on mine now seems redundant, even like posing. I just didn’t like it. There it is.

That description of The Vivisectors as if Mervyn Peake wrote The Human Stain! I was pretty bowled over by Williams’s project with The Doloriad but it is a deeply discomfiting novel. It pleased the lit student in me immensely though. I’ve been looking forward to this one for quite some time.